Warning: This article is a bit different from my previous ones as it requires the reader to have some programming experience.

Allow me to start with a question: have you ever seen or written such a comment?

// Make sure to use `is_valid()` before Or perhaps a slightly different version

Exception(...) Cannot do X in state: YYou probably have plenty of memories of forgetting to do some kind of ceremony before calling a function, maybe even asking a colleague if some function was safe to call at some point.

This class of issues can even be hidden into more complex business flows with multiple layers of indirection, enabling some invalid paths to be taken, causing critical business logic issues.

Creating an order

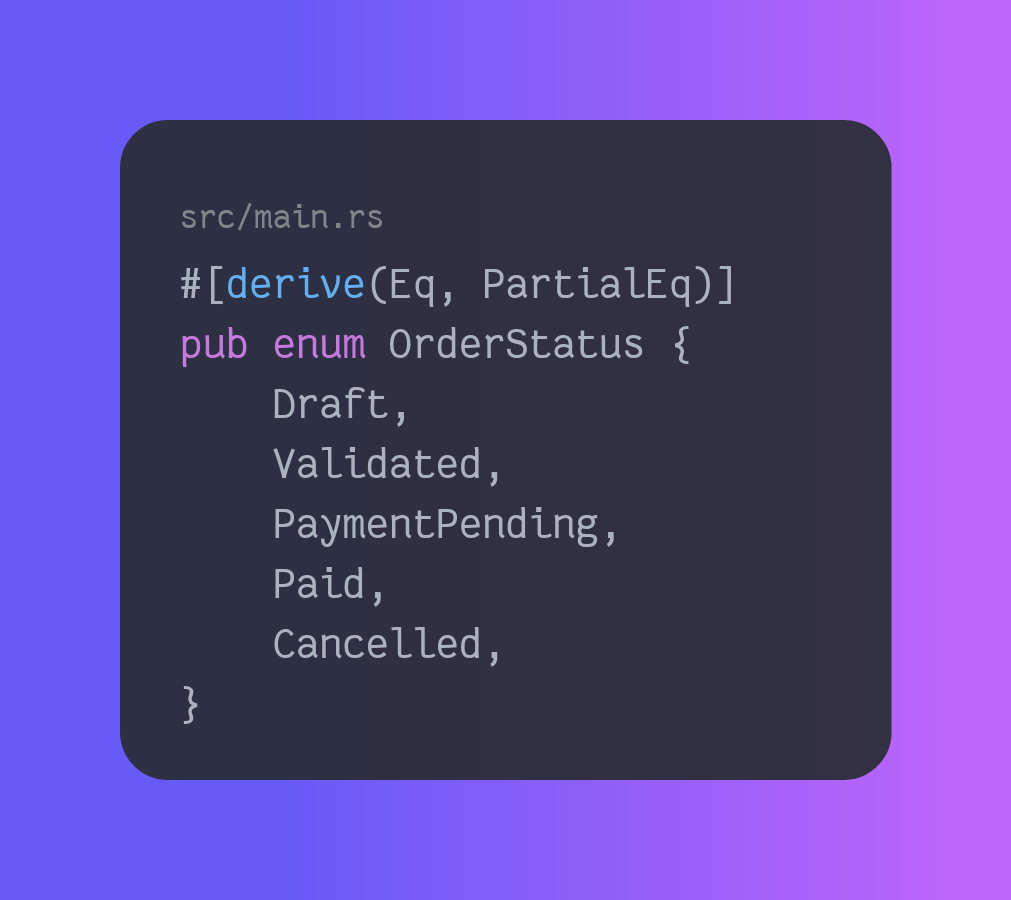

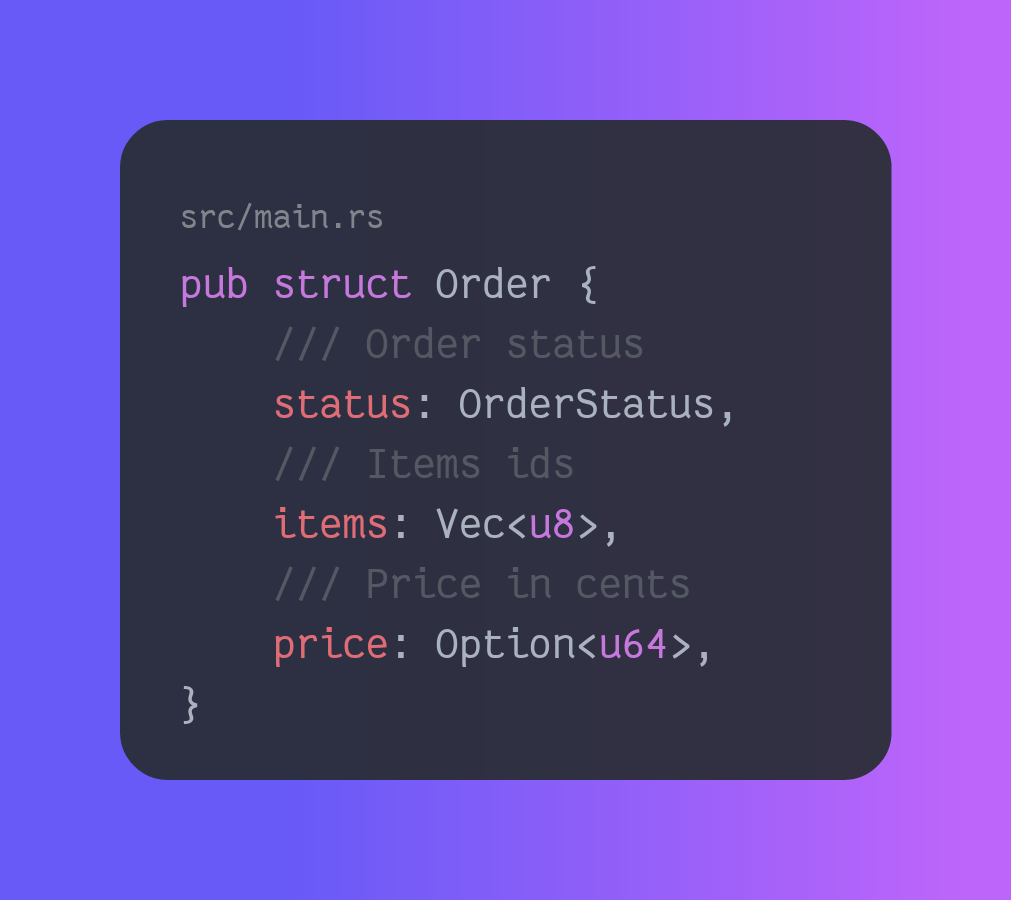

We have received requirements to build an order system. We should have the following states: draft, validated, payment pending, paid, and cancelled. Our clients have asked that we should not be able to cancel an order in payment, or if it was paid. Let’s get to work, first we’ll define our states as an enum, and create an Order struct to hold our data!

We created an enumeration of our states and a structure to represent our order, the next step is to implement our logic.

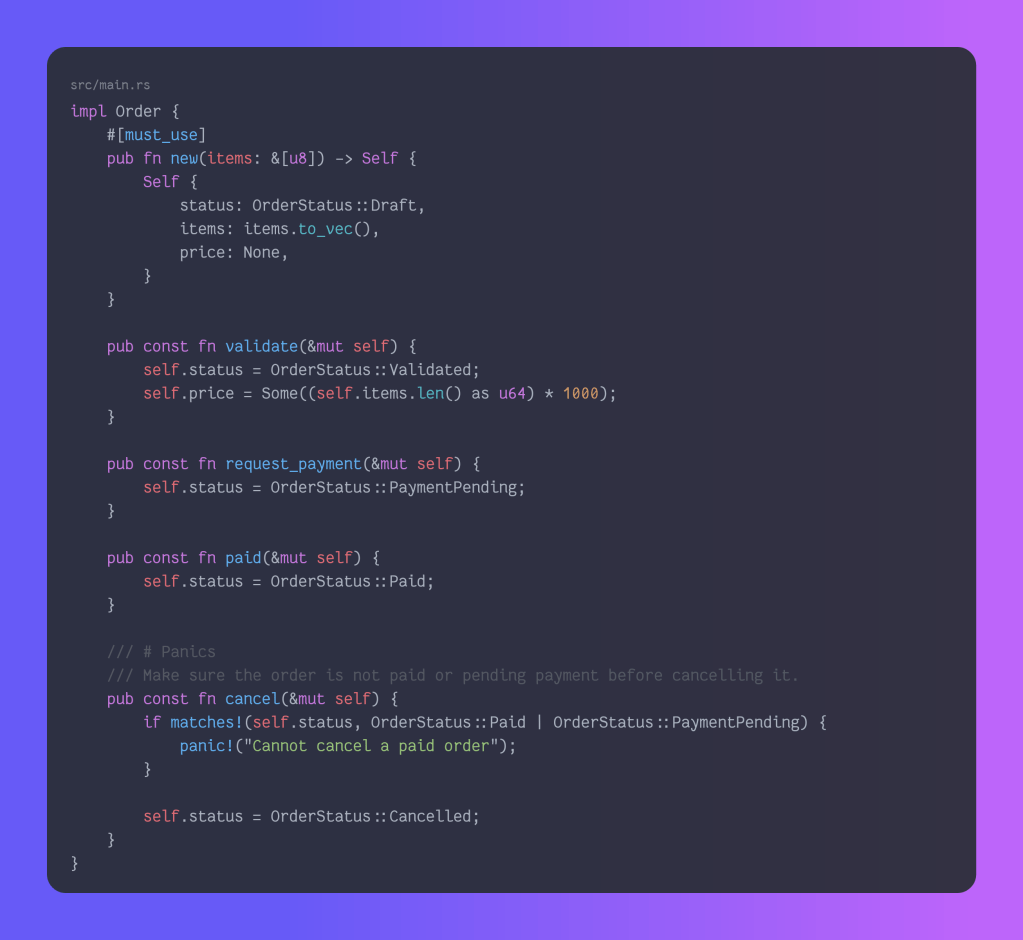

For the sake of the snippet not being too long, the code is rather naive; any getter/setter code is omitted. However, it should be sufficient to understand the issues at stake. One could add a check for state at the start of each function and an exception saying, “Cannot do X in state Y”.

In our example, the user has to handle all the cognitive load of which function he can call, which action has to be done next, and also has to satisfy preconditions all on his own. In our case the code is rather simple, but for large business workflows, sagas, etc… This gets complicated quickly, and will often end up with a runtime exception.

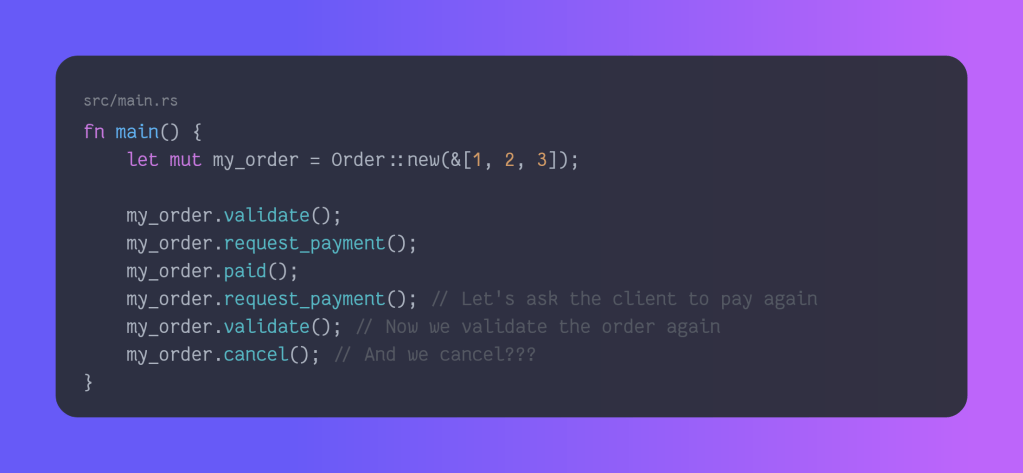

This kind of code will also slow down handovers, or junior members of the team. To see just how bad this can get, look at what the compiler happily accepts:

This feels quite odd, as we do have all the requirements, and we know which actions to take in which states. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could somehow encode this information and guide the user? Or even better, prevent him from making a mistake altogether! So how do we fix this?

Type state encoding

Let me show you how to encode your order flow in types. Examples are in Rust but you can achieve the same result in most modern programming languages; for example, since Java 17, sealed interfaces can allow you to achieve the same result.

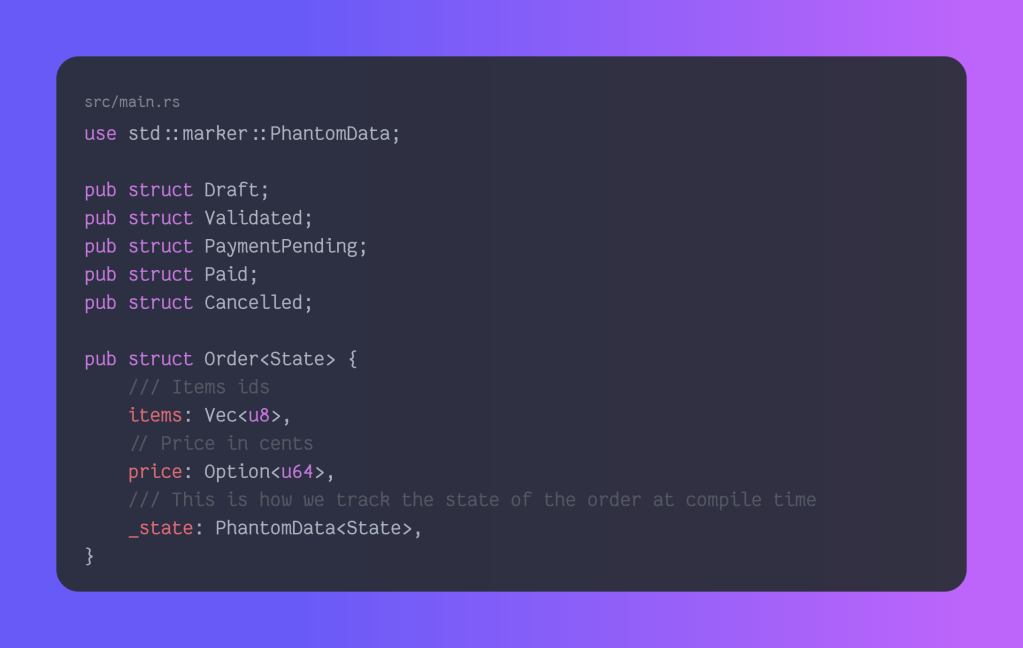

First we create our different states, and then we will create a struct order, which can act as an order of a given state. You can read more about PhantomData in the Rust documentation. The equivalent in Java would be to create an interface order and then extend it on draft, validated, payment pending, paid, and cancelled.

This is our draft state implementation. We allow the users to create a draft order, and we allow them to either validate, which here doesn’t do much but compute the price and, most importantly, returns an Order<Validated>. The other option is to cancel the order, which returns an Order<Cancelled>.

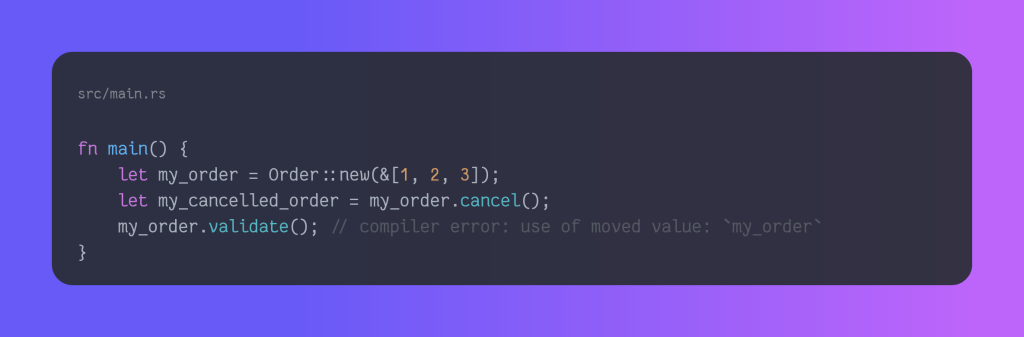

I would like to point out to the reader who is not familiar with Rust that the fn xxx(self) will take ownership, which is a Rust term meaning that the caller won’t be able to use the object anymore. This ensures us that once the order is cancelled, we won’t be able to use an old reference and validate it. Here is a demonstration.

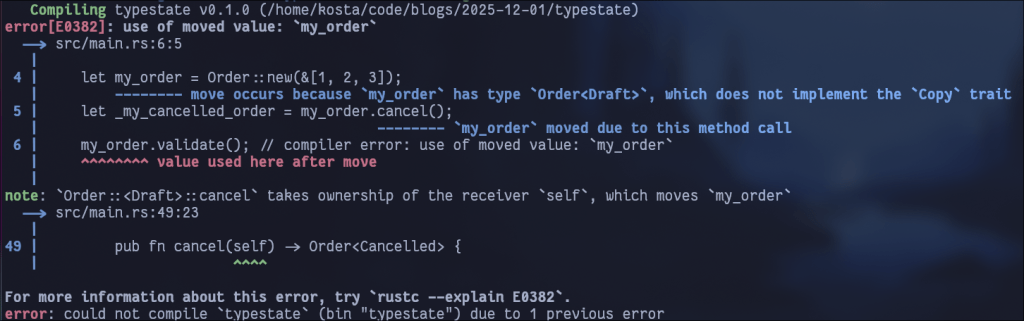

The compiler catches this mistake for us:

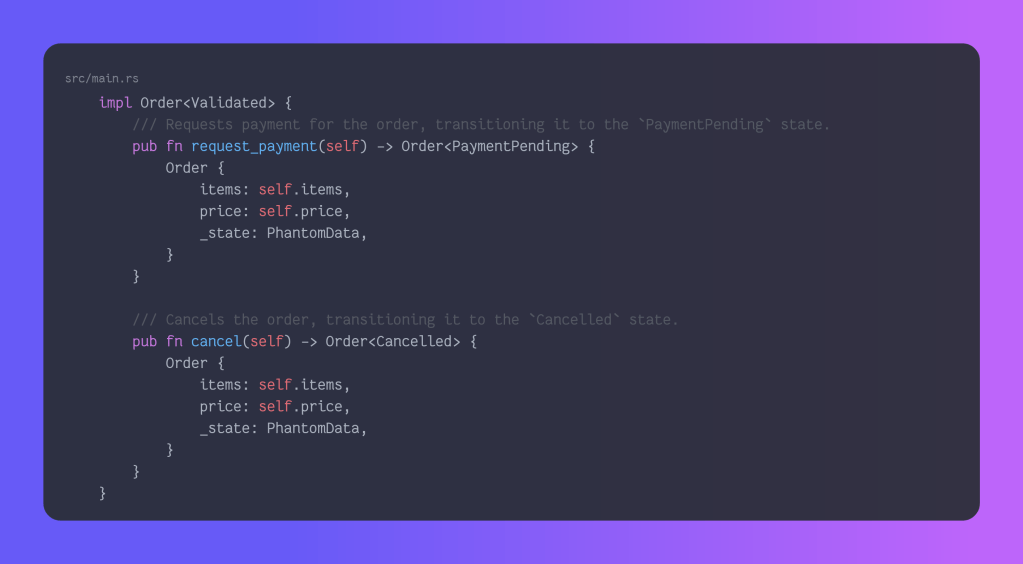

Now let’s implement the validated state:

We would rather not allow anyone to create an order that is already validated, so we just omit any new function. Furthermore, we only want to allow the user to request payment and to cancel the order.

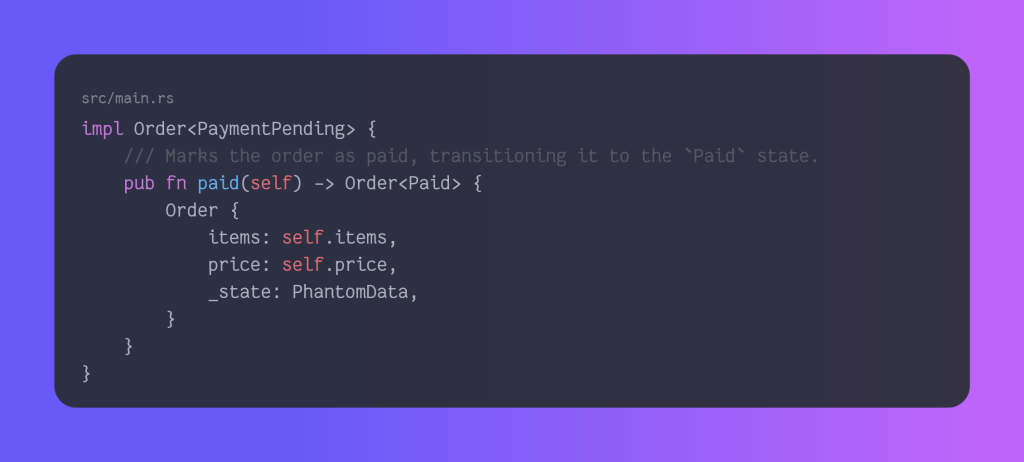

The last step is payment pending, which only has to mark the order as paid.

We are done, as we don’t have anything to do if the order is done or cancelled. That was a bit of work, but now let’s see what we achieved!

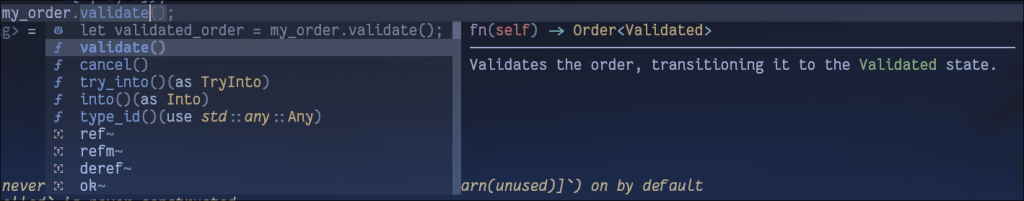

After creating an order, your IDE can help you with what is possible, and you can only perform valid actions. Any non-valid action is not possible, as the function does not exist to perform it.

Here is our happy flow in action

Pretty neat, right? The compiler now enforces our business rules, and the IDE provides us guidance for free. Let’s see if we can solidify our knowledge!

Going further

Now that you have seen type states in action, it’s time for you to try it by yourself!

Add a payment_failed function.

- Transition back to payment pending.

- Create a new payment failed state.

After implementing both, see how it affects your state graph and how each approach could be useful.

You can also try to add a maximum failure count.

Conclusion

The type state pattern is a powerful and versatile tool that allows you to keep the complexity inside the code instead of in comments or the maintainers’ brains! It does come at the cost of some boilerplate, but I think it’s well worth it.

Leave a comment